When financial markets decline suddenly, everyone becomes an economist explaining what is happening and why this time it is different than all the downturns that came before it. The downturn of 2022 may turn out to be a normal market correction in one of the most sustained financial bull markets in a century. But it could also be only the start of a prolonged term of financial setbacks that has been creeping up on us for years.

The private technology industry is not immune to macro-economic changes. There are four intersecting dynamics we should pay attention to:

- Macro-economy

- Inflation, government debt and money supply

- Interest rates

- Finance and equity valuations

Technology entrepreneurs are most interested in the ability to finance and equity valuations. However, they need to understand how the other three factors affect valuations, financing and exits.

Macro-economics: Since the recovery from the Great Recession in 2008, the North American economy has been on a tear. It’s been fourteen years without a major economic contraction, other than the pandemic quarters of Q1-Q2 2020. While not minimizing the savage effects of the COVID pandemic, the economy rebounded quickly to recover most of its losses. Now, scarcely two years after an imminent meltdown, we are in an economic boom.

There are differing opinions on whether the good times will continue. Optimists look to the current spate of “revenge” travel and spending as people emerge from their pandemic cocoons. As COVID restrictions are lifted and supply chain issues resolve, the boom should strengthen.

Pessimists point to many risks that are growing stronger by the day: Inflation has increased swiftly in recent months, prompting the central banks to rapidly raise interest rates. If inflation does not cool, interest rates will have to continue to increase, slowing the economy. If inflation is persistent, then it gets baked into wages and prices making it even harder to reverse.

Supply chain disruptions may persist. As the virus continues to mutate, new strains will continue to cause outbreaks. If China’s response is to continue to impose harsh shutdowns, supply disruptions will continue, exacerbating inflation and slowing the economy.

The war in Ukraine is already causing havoc world wide. As soon as the invasion began, gas prices instantly rose to their highest levels in history. The war may continue for a long time as Putin refuses to accept defeat and the Ukrainians continue their fierce resistance. The uncertainty about the outcome, its time frame, and sanctions on Russian oil exports may keep energy prices high, further cooling the world economy.

While the economy is booming now, tech entrepreneurs should not base their business plans on a continuing robust economy.

Inflation, Government Debt and Money Supply: After decades of inflation below 2%, the consumer price index (CPI) began to increase in the fall of 2021. Central bankers called this sudden and unexpected inflation “transitory”, a short-term response to supply chain disruptions caused by COVID shutdowns in China and rising fuel prices. These external factors would resolve themselves in the near term. However, there was another factor that was only rarely mentioned: the massive expansion of the money supply. In the Great Recession in the late 2000s, and again during the pandemic, the central banks created hundreds of billions of dollars in Canada, and trillions in the US, to stimulate the economy to avoid an economic meltdown. Governments quickly ran up massive deficits to sustain people and businesses. Monetary and fiscal stimuli were necessary and successful moves. Our economies would have collapsed without them.

But there was a downside to these measures. The bankers and economists said that there was enough slack in the economy to absorb the stimulus without increasing inflation. Few people questioned this analysis. However, it should have been obvious that if you pump massive amounts of money into the economy, then at some point, you end up with more money chasing fewer purchases and prices will naturally increase.

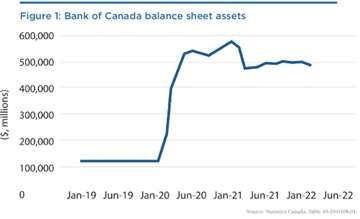

Look at the graph below:

The money supply grew from $100 billion to nearly $600 billion at the height of the pandemic. This is a massive expansion with significant consequences for the economy, inflation, exchange rates, and interest rates, but until very recently, has been mostly ignored. Through the second half of 2021 and the first half of 2022, the bankers and economists kept to their story that inflation was a transitory event which would decrease as soon as the supply chains were repaired. Few experts explored the impact on inflation of a 6-fold increase in money supply; a problem which is not transitory.

To their surprise and concern, inflation kept growing. In late 2021 and early 2022, the Canadian inflation rate rose quickly from the 2% – 3% zone, where the bankers are comfortable, to 7.7%, a rate not seen in forty years. Central bankers are now admitting that inflation is a bigger problem, not transitory, and caused, at least in part, by domestic factors. They are hinting that inflation may increase further until it is under control again. With $600 billion flowing through the economy, inflation may be very difficult to control.

This is not the first time that bankers expanded the money supply to stimulate the economy to stave off a major recession. They did it in the early 2000s in the wake of the dot-com crash. At that time, the excess cash went into real estate and billions of dollars worth of mortgage derivatives. These excesses nearly cratered the entire financial system in 2008. With that recent history, it is curious that the bankers didn’t anticipate the inflationary after-effects of the current round of monetary expansion.

Tech entrepreneurs should consider the impact of sustained inflation on their businesses. Do they have the power to increase prices as fast as their costs increase? Or do they need to consider managing with shrinking margins? Managing the cost and price structure will become increasingly important.

Interest Rates: To combat inflation, the central bankers started to raise interest rates, something they had not done in years. By increasing the cost of borrowing, the bankers hoped to reduce the demand for money and lower interest rates. At the time of writing, the Bank of Canada had just raised rates by 0.5% (double the normal adjustment) to sit at 1.5%, with more hikes to come.

The bankers are now fighting inflation hard. But raising interest rates reduces borrowing which cools the economy, slows growth, and increases unemployment.

There is another concern: as interest rates rise, the amount of money that governments must spend to service its huge debt pile also grows. This results in less money for other government priorities, including health care, government income supports and research spending, among many other priorities. Any decreases in spending or increases in taxes reduces economic growth, thus exacerbating the problem.

The size of government debt in Canada relative to the size of the economy is at the highest it has been since World War II, driven by massive government deficits and financed by the massive monetary stimulus from the Bank of Canada. That’s a lot of money circulating in the economy driving inflation higher. The last time we were in this situation was the early 1980s. The central bankers overcame inflation exceeding 12% by hiking the interest rate to over 20%! It was painful at the time, but ushered in 40 years of declining inflation and interest rates to which we have all become accustomed.

Can the bankers do it again? They have conceded that containing inflation through higher interest rates will not happen quickly. Given the size of government debt and the money supply, the inflationary pressures are huge. The bankers have said that more interest rate hikes are coming, that the increases might be larger than the recent hikes of 0.5%, and the rates might have to exceed 3%, which they previously indicated was the highest rate necessary to control inflation. How high will interest rates have to rise to contain the beast of inflation? Given the monetary surplus, it will be difficult to control inflation. We should expect much higher interest rates and for a much longer time, and the possibility of a deep and long recession.

But on the other hand, maybe the inflation problem is not as serious as this. Some pundits point to the spread in the yields of long-term, ten-year Canadian bonds between real rates (i.e., rising with inflation) and nominal rates (i.e., fixed rate of return regardless of inflation). Real rate bonds are yielding 3% compared to nominal bonds yielding 1%. This suggests that bond traders are anticipating long term inflation at 2% and believe that the bankers will get inflation down to that rate within the next few years.

Finance and Equity Valuations: Technology entrepreneurs over the last couple of decades have been blessed to live in an economy that was flush with cheap money. Start-up and expansion capital was relatively easy to obtain and valuations soared. Entrepreneurs could start, scale and sell companies in only a few years at excellent valuations.

But that could change soon. Inflation and interest rates could have a direct impact on the appetite for acquiring tech companies and the valuations acquirers are willing to pay.

We have already started to see the impact. The equity markets have declined precipitously since late 2021. The NASDAQ index of public tech companies slid 30% from November 2021 to May 2022. Some of last year’s tech darlings, like Shopify, are off 80%. In times of turmoil, public markets start a “flight to quality”, i.e., leaving the tech sector and its potential unicorns for the safety of more predictable companies and industries.

M&A activity in general declined significantly in the first half of 2022 from a year earlier, but then 2021 was a banner year in M&A. Activity in 2022 is about at the same level as in 2019 before the pandemic, so there is no indication yet of a chilling of the M&A market.

Fortunately for tech entrepreneurs, at least for the moment, private early and growth stage tech companies are not directly affected by the corrections in the public market. Venture capital (VC) companies, private equity (PE) firms, and large tech companies are still flush with cash. The VCs and PEs raised money when it was plentiful and are still sitting on lots of “dry powder”. Big Tech has earned billions in profits. All are waiting for the opportunity to acquire promising private tech companies. As long as capital is plentiful, acquisitions will continue and valuations may not be affected much.

However, if interest rates and inflation remain high, a chill will eventually set in on the M&A market for private technology. Buyers will become choosy, activity will slow and valuations decrease, reducing the number of acquisitions and the valuations paid. We can certainly expect to see the the revenue multiple on SaaS companies to continue to retreat from the stratosphere. In 2011, the value hit 16.9x, but fell to 10x in early 2022. There should be further declines.

In the longer term, sustained higher interest rates will give investors more options. They will not be in a position of “chasing yields” as they were forced to do when interest rates were low. Consequently, VCs and PEs may find it more difficult to raise their next funds, reducing the amount of investment capital and the prices they will pay for investment and acquisition.

As the capital chill works its way upstream, private tech companies may find it harder to raise start up and expansion capital from VCs. Even though they may be a long way from exit, VCs may argue that the M&A chill will reduce their exit valuation. To earn their required return, they will have to reduce valuations paid earlier in the investment cycle. As a result, while private tech valuations may not be affected in the near term, any evidence of a chill in the M&A market could result in declining valuations and fewer exits.

What Should Tech Entrepreneurs Do? There is an aphorism that financial markets climb a wall of worry. Currently, that wall is getting bigger: inflation, money supply, interest rates, war, energy prices, supply chain disruptions. The difference this time is that there has never been this quantum of money in the economy driving inflation and interest rates. Solving this problem will be a challenge.

But maybe we will climb over the wall as we have done many times before. Maybe the current economic boom will continue, the pandemic will recede and shutdowns will diminish, supply chains will be rebuilt, the war in Ukraine will end, and the fiscal and monetary issues will remain manageable as they have in the past.

But anchoring your business plan on a series of optimistic outcomes is risky. Entrepreneurs should not be surprised if inflation and interest rates stay high, growth slows, financing becomes harder to find and negotiate, valuations decrease, and there are fewer exits. Entrepreneurs contemplating an exit should put plans in place now while there is still lots of dry powder and an appetite for acquisitions.

In managing the business, entrepreneurs should prioritize generating cashflow from existing products and services rather than investing in higher risk expansions. Development should be focused on incremental, low-risk product enhancements rather than the next x.0 release.

Entrepreneurs considering starting a business should rely on bootstrapping, and maybe investment from friends and family. A strategy contemplating successive rounds of investment should be reconsidered as the next round may not be available on favourable terms, if at all.

Final Words: The economic fundamentals may be more at risk than the bankers, economists and politicians let on. But they managed through the terrifying near-meltdown in 2008 and have that experience as a guide. While they focus on the macro-economic challenges, tech entrepreneurs should continue to manage their businesses in a scenario where that the buoyant M&A market may become less exuberant.